Damascus Countryside — Once you cross the Harasta-checkpoint, set up at the western entrance to the city of Harasta, eastern Ghouta, coming from Damascus, a sense of alienation from the capital city would overcome you, that is only 15 minutes away by car. Harasta today is nothing like the city it used to be, for 80% of it gave way to destruction. Its features are changed and identity obliterated.

In his hometown, Abu Abdo al-Harastani (pseudonyme) tried to renovate his collapsing home in the city of Harasta over and over again, and failed every time. He returned to the town in Harasta city in eastern Ghouta, east of Damascus, in the wake of the “reconciliation” agreement, signed in 2018 by the armed opposition groups and the Syrian government.

His renovation efforts were of no use because his house was out of the city’s urban land regulation plans.

Having returned home, the forty-something old man tried to claim the authority’s permission to renovate his house legally, countless times. However, a decision passed by the Harasta City Municipality stood in al-Harastani’s way, as it ordered that “renovation and building works at the uncontrolled squatter areas be frozen.” Today, the man and his family live in “a destroyed, windowless, doorless home. The walls are cracked and the whole building is at the risk of falling apart.”

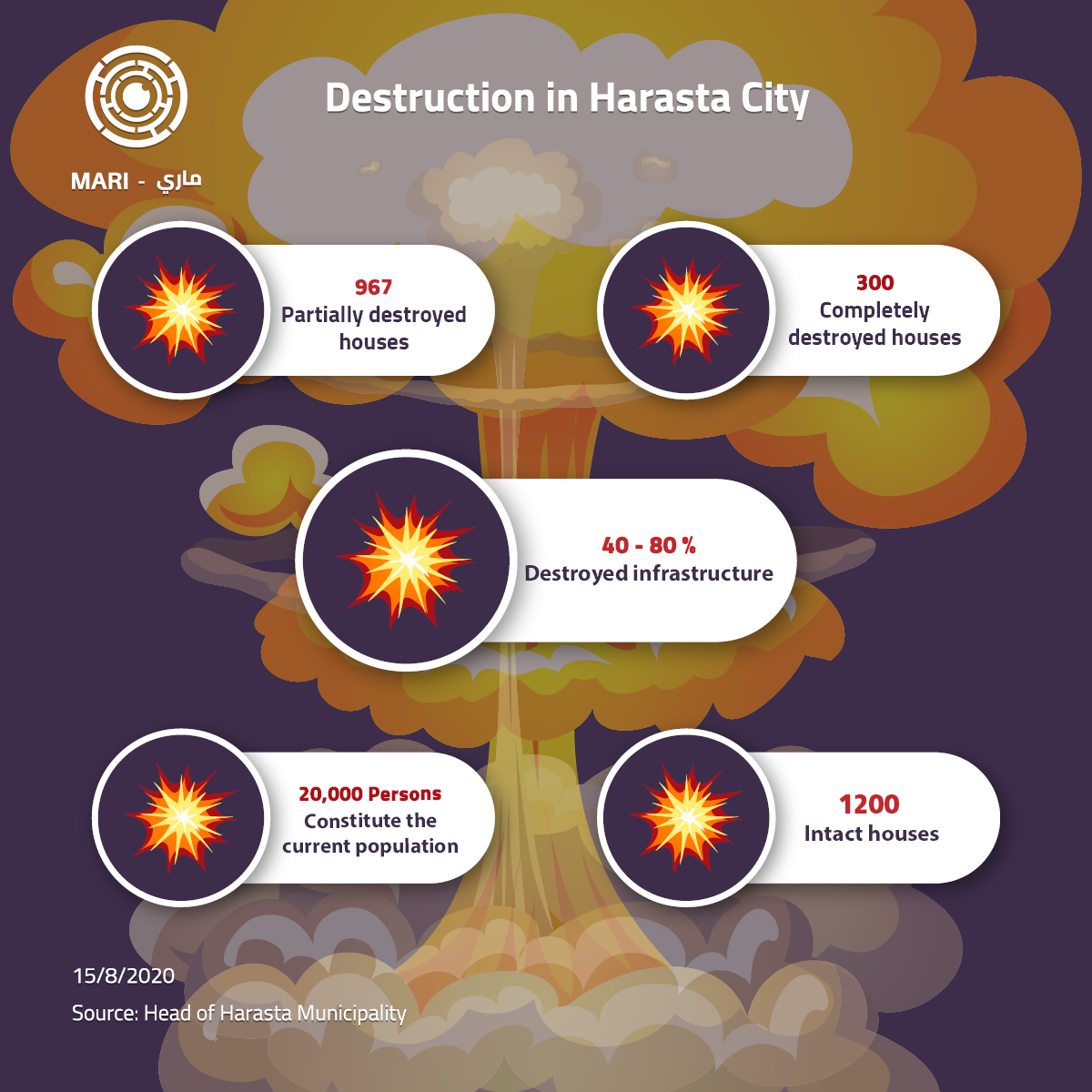

To their misfortune, hundreds of Harasta’s residents share al-Harastani’s fate, as they stand looking at the political landscape, which promises a shift in the conflict from militarization to a strife for survival and sustainability, to be initiated by the city’s remaining residents. About 20,000 persons constitute the city’s population now, as the pre-war figures dwindled from 250,000 persons. The lasting population is facing a desperate shortage of services.

In fact, an end to the war is not necessarily an end to the poorest people’s suffering, for they actually start a new journey, no less painful, as they struggle to eke out a living, surrounded by mountains of rubble and war remnants.

No renovation for squatter areas

To allow the renovation of destroyed houses and stores, the Harasta City Municipality stipulated that affected people (owners of the property) apply for renovation at the Municipal Affairs Office. Al-Harastani stuck to the rules, upon returning home. Nevertheless, his application was denied, since his house was located outside the borders that the urban land regulation plan of Harasta city covers. “Hundreds of other renovation applications, however, were approved, for houses within the plan’s [scope],” Adnan al-Waze, head of the Harasta City Council (Municipality), told Mari.

“Renovation proceedings are referred to the Technical Office, which conducts building inspections. If the sought renovation work is simple, so is the harm, the Executive Office grants renovation permits based on the Technical Officie’s report,” al-Waze said. “Regarding people in the squatter areas, a letter was sent to the Provincial Directorate, which answered that no renovations were to be conducted at unauthorized areas, so that agricultural lands do not end up as a block of concrete.”

“However, rubble removal and patching large gaps in several buildings was allowed,” he added.

“The Damascus Countryside Provincial Directorate has suspended all authorizations for the time being, waiting for new decisions from the Regional Committee,” al-Waze told Mari, adding that “the committee was founded to study the reality of the urban land regulation plans in Damascus Countryside,” headed by the governor. As members, the committee encompasses directors of technical and legal service directorates, head of the Provincial Council, deputy director of the Executive Office, director of the Administrative Unit and the Municipal Technical Office, as well as the delegate of the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, which is to follow-up the set up regulatory plans.

These measures mean nothing to al-Harastani, and many others like him, whose homes fall outside the municipality’s urban land regulation plans. Al-Harastani was, thus, coerced to apply a few primitive renovations to his house, using a few wooden boards and nylon instead of windows. These modest renovationtions will protect him from neither the scorching heat, nor the piercing cold.

Furthermore, none of Harasta’s returnees was made repatriation for the damage so far, al-Waze reported, stressing that “the Damage Committee of the Damascus Countryside Provincial Directorate had carried out a field scan to assess the scale of destruction and property damage to compensate the affected persons.”

“The affected people were not offered any compensation since,” he said.

Al-Harastani was not the only person deprived of the right to renovate his home, according to statistics the municipality head reported to Mari. Some 1000 people are equally doomed, unable to change their reality, given the government negligence, or seek refuge in other places. Consequently, they continue to live in derelict neighborhoods.

80% of buildings are cracked

“Buildings in military hotspots, including Harasa, are weak and cannot hold the intended renovation or maintenance work,” Engineer Humam Hassan said, attributing this to “intense bombings and confrontations, which inflicted drastic damage on infrastructure in the majority of these areas, [which witnessed military operations], estimated at over 60 to 70%.” In Harasta, however, the damage amounts to 80%, he stated.

“On average, 40% of the city is destroyed,” Adnan al-Waze, head of the Harasta City Municipality, said.

“If it is an area-level renovation that is intended, government efforts must be invested, not personal ones, by the affected people who lost everything they once had,” Hassan, an engineer at the Urban Planning Directorate in Damascus Countryside province, told Mari. “Moreover, such renovations require specialized technical studies and consultancies that examine the underground, [the infrastructure], the cracks and fissures which might jeopardize the renovated buildings in the future.”

Debris removal

Small debris removal operations were conducted, major streets reopened and a number of severely damaged buildings demolished, al-Waze claimed.

“Nonetheless, there are countless tottering buildings, [which are at the brink of collapse], posing a threat to people’s safety,” he added, stressing that he repeatedly demanded the removal of these houses, and others that are totally destroyed, but his calles were “all to no avail”.

On the same note, al-Waze said that 160,000 m3 of debris were removed from the city’s streets, 90,000m3 of which were deported in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the remaining 70,000m3 were, however, removed by the General Corporation for Roads and Bridges of the Syrian government, adding that the Harasta Municipality needs debris removal contracts, which are yet to address no less than 280,000m3 of solid waste.

“Shameful” services

Al-Wez admits that services are poor and modest, especially as they are provided to the city’s population, as large as 20,000 persons. “There is a pressing need to remove debris and implement drainage and sanitation projects, for drainage systems were severely damaged due to the tunnels dug by the armed opposition groups when they were still in the city, particularly since many houses are about to collapse and must be promptly demolished.”

In late December 2019, numerous severely affected buildings collapsed in Harasta city, reported local media outlets, stating that the buildings yielded to the torrential rain, and given the fact that “residents were unable to renovate their houses properly.”

Worse yet, the hampered debris removal urged several families to abandon their homes, al-Waze said. “The city’s [state] bakery must also be reoperated,” he added, as it only lacks oil and flour supplies now. “The bakery is ready for production, but it has not been operated yet.” The families, for their part, are getting bread from a privately owned bakery.

Moreover, the city’s electricity sector is poorly functioning, for power transformers are needed to resupply neighborhoods with electricity. Concerning healthcare, the city is denied services after 3 pm, for the only two mobile centers run there are operated according to a strict schedule.

Tragic sight

Paying the city a visit is not that easy, for Harasta, like many other Syrian areas, is infact inaccessible. You have to stand in line and wait for about an hour, until the checkpoint is done with the entry measures — that is the inspection mechanisms adopted by the Syrian regular forces at each of the city’s entrances. Identity documents are examined, cars and luggage are inspected.

Once you are in, the first street to see is al-Mahkma, which buildings are either renovated or are not destroyed at all. The street has not witnessed the horror of acute battles suffered by other streets, you would wonder. You turn left, and then right, in a blink you are back in time to besiegement, as if transported there by some sort of a time machine. The streets back-then were motionless and depopulated.

Your nose also starts to run, as it gets stuffed with dust that fills the place, for the destruction is massive on those streets. You walk alleyways that do not fit cars. Semi-houses and destroyed ones, you pass by them, reaching the Harasta Cemetery. The cemetery itself is damaged, as if the last witness to all that once happened there.

The drainage holes are extremely large, some are venen five meters wide. Electricity cables are either cut or stolen, leaving the people no other choice but reconnecting them on their own. Separately, each of the families would run extensions from the power transformers set up at the city’s entrance, all the way to their homes. That is several of the afflicted city’s streets will continue to live in the dark. There is also the rationing dilemma, for some power cuts might continue for 15 days in a row, a number of Harasta city’s residents told Mari. Even though it is daytime, the city appears as if haunted by ghosts, striking fear in the hearts of its visitors. Then, what feelings does it inspire in its residents at night?

Hope of renovation lost

“At the first phase, humanitarian organizations plan to renovate 3,000 houses in 2019. The number might rise to 5,000 houses towards the end of the year [2019],” Tayseer al-Qadiri, director of Relief and International Organizations Directorate in Damascus Countryside province said on May 13, 2019.

“The plan first targets the area of Mughr Al-meer in Mount Hermon, western rural Damascus, and several areas in [eastern] Ghouta, including Ayn Tarma, Arbin , Harasta, and al-Darbakhiya. Site selection, however, depends on necessity and the urgency of returning people to their homes. None of the areas is excluded,” he said.

Commenting on this, an inside source from the Local Councils Directorate in Damascus Countryside province told Mari, on the condition of anonymity, that “the international organizations’ renovation plan and reconstruction is in fact modest. It is limited to certain areas and historical sites, which can be attributed to political reasons.”

“The Harasta Municipality and the Damascus Countryside Provincial Directorate are unable to provide necessary infrastructure, such as services and public utilities, given the government’s inability to afford reconstruction, let alone the people whose circumstances are so tragic, that they were forced to live in almost destroyed houses,” the source added.